A few days ago, on Facebook, Cuban doctor Víctor José Arjona Labrada denounced the authorities, declaring that his mother —a teacher with 46 years of experience— had died because police guarding an MLC store refused to take her to the hospital. The physician had asked the officers for assistance, aware that waiting for an ambulance in Cuba requires the patience of Job.

Just a few days after this incident —which probably would have been prevented if Cuba's ambulance service functioned properly— the company Transtur announced on the same social network, without batting an eyelash, the importation of 800 new cars to support tourism.

We talk a lot about the Cuban economy, seeking to unravel the reasons (usually hidden or distorted) why and to what end Castroism makes the decisions it does, a succession of missteps that undermine even its own stability.

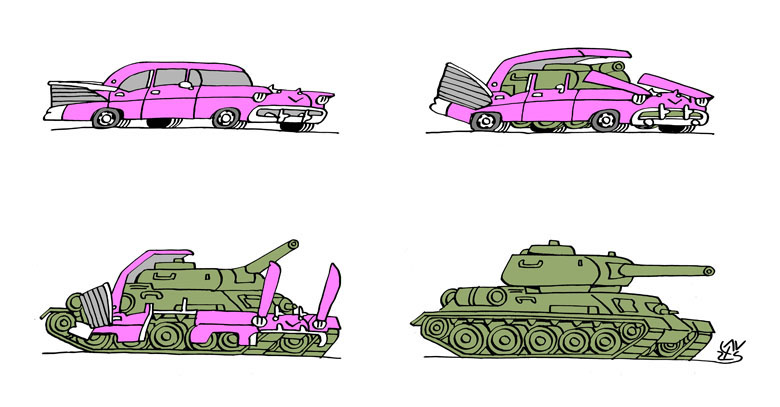

The most shocking bit of economic data of late has been the state's appallingly lopsided investment in tourism and related activities, while the due scrutiny has been lacking that would reveal the hidden side of a system that purports to be of the people and for the people, while importing rental cars but waiting timidly to see whether someone will donate ambulances to it.

Specifically, in Cuba the "Business Services, Real Estate and Rental Activities" category is allotted, according to data from the National Statistics and Information Office, 57 times more investment than Public Health, 15 times more than Agriculture, and 76 times more than Science and Innovation.

While the country's capital is crumbling —including a visible deterioration of its prioritized Historic Quarter— and deficient, insufficient sewerage and aqueduct systems plague the city, 45% of all national investment is earmarked for new tourism-related construction. Why and what for?

The simple answer is: because they can. Although it may seem tautological, it is vital to note that in Cuba a military/bureaucratic oligarchy decides absolutely everything, without being accountable to anyone, so it is not redundant, but rather important, to highlight that in the midst of the greatest health crisis in history, with thousands of Cubans dying in run-down hospitals lacking basic medicines, the Castroist government continued investing in tourism at the same frenetic pace as in previous years. This fact, by itself, defines what a dictatorship is.

This government’s "obsession" with tourism investment has no coherent economic basis:

- Hotel occupancy was already in decline before the coronavirus pandemic; it makes no business sense to increase supply when demand is falling.

- A more equitable distribution of investments, for example, buoying Agriculture and Industry, would have favored a more balanced economy, even making tourism less dependent on imports and more profitable, and would have, additionally, furnished the population with more food and goods, which would have eased social distress.

Thus, the explanation is eminently political; it should be noted that, although the tendency to prioritize hotel investment over everything else arose under Castro himself, and has been sustained under Neo-Castroism, the reasons for this support are different.

Castroism

The only thing that Fidel Castro knew about economics is that he could not allow a civil society based on a community of prosperous owners. Rather, he needed everyone dependent on the Government; that is, on him.

Thus, he compromised the country's foreign policy to ensure a foreign supplier of resources for himself, which allowed him to destroy/nationalize the nation's economic fabric, as Fidel had no interest in developing the internal economy, which would have required market freedom and an unacceptable loss of power.

The USSR and Venezuela fulfilled this role, rendering Fidel Castro independent from the people, and the people dependent on him. Real resources were obtained by the Government, which spent and invested them in the interests and on the whims of the boss, while the internal economy was a fiction to keep people distracted.

When Castro I lost the USSR, he allowed - out of extreme necessity - some economic freedom, but he quickly backpedaled and, almost simultaneously (in the mid-1990s) discovered that the development of tourism could allow him to maintain a state regime in which he was the state, as Castro-style tourism features characteristics similar to an external source of resources:

- The profits generated go directly to the government's central account.

- It is developed with foreign partners without any domestic, private, capitalist participation.

- It is centered in enclaves that are relatively isolated from most of the people.

- It was conceived in a way disconnected from the internal economy: just hotels for sun-seeking beachgoers.

- Cuban workers are paid little, granted some moderate privileges, but kept dependent.

- Cubans could not access them even by paying; it was a private business owned by the State ... by Fidel.

When Chávez came along, tourism was not abandoned. What was reduced or blocked was any kind of economic liberalization. Tourism investments, in fact, actually intensified, using resources stolen from the Venezuelan people. The important thing was to renew the scheme to obtain resources independent of the internal economy, which was kept, intentionally, inefficient: instead of a welfare state, the aim was the welfare of the state.

Neo-Castroism

As a necessary Cuban counterpart complementing his foreign partners investing in tourism, Fidel Castro turned to his most loyal subjects: the Armed Forces, administrated by his faithful younger brother.

But then the inevitable happened: separate interests were created in that structure that, as Emilio Morales has noted well in his articles, has become a mafia in and of itself, crystallized in the form of GAESA, an entity semi-independent of the Government that shamelessly and unscrupulously seizes the country's assets to invest them in what is under its direct control: tourism.

Neo-Castroism, introduced by Raúl Castro and supported by this mafia-like structure, showed early signs of wanting to change Fidel's inefficient, centralist system. There was a fleeting moment, a mirage when it seemed that rapid and decided economic liberalization would be undertaken to seriously revitalize the national economy, for the first time since 1959, but everything fell apart due to fears of "going too fast" and Castro II's ineptitude.

Today in Cuba those who control the country's weapons also do its money, but they must coexist along with a bureaucratic leadership that dominates the internal machinery of political power and legitimacy providing the regime with stability; this "mortar" is Neo-Castroism.

Looking at the national investment figures, it seems that their scheme is for Díaz-Canel and the bureaucrats to use their half to sustain, for as long as possible, the tragedy of the country they have charged with governing. Meanwhile, López-Callejas (the head of GAESA and Díaz-Canel's "advisor", as well as a member of the Castro family) is to use the other half of the loot to build as many hotels as he can, in case one day the house of cards collapses so that he has a good cake to cut up and divvy out to relatives, collaborators and accomplices.

The obscene imbalance in the state's investments is not some kind of blunder in the regime’s economic policy, but rather a deliberate result in a country that is devoid of democracy preyed upon by a bloodsucking oligarchy of hangers-on and military brass.