The Cuban regime has been fretting for month over "Patria y Vida", the song that has said "It's over!" to it, inspired graffiti, and provided protests on the island with "ammunition" The video boasts over three and a half million views on YouTube one month after its debut. But, beyond the figures, the song promises to be the biggest hit in Cuba during this year that is just beginning. In this article we tell you how it came about.

The original idea for "Patria y Vida" came from Yotuel Romero, a former member of Orishas, who invited the artists of the duo Gente de Zona, the singer-songwriter Descemer Bueno and the unruly rappers Maykel Castillo "Osorbo" and Eliecer Márquez "El Funky", both residents of Cuba.

"We had done 'Ojalá pase,' which was this remix that I wanted to make of 'Ojalá' (a Silvio Rodríguez song). I called Randy, and Alex, and we started working on the song. Then we called El Funky, Descemer and Osorbo. When I saw that the song had something magical, I thought of Silvio, and I was struck by that," Yotuel told DIARIO DE CUBA.

"The message now 'It’s over' rather than 'Hopefully.' It hurt to remove that part because my wife sang it beautifully. She helped me write it," he said, referring to the Spanish singer Beatriz Luengo.

According to Asiel Babastro, the director of the video, Luengo's inclusion may have sparked some disputes because "she's not Cuban and maybe people didn?t take that well." Babastro explained that there had been no plan to exclude women, nor for all the performers to be black.

"There was no woman, there is no woman in Cuba or anywhere that is a high-profile rapper or reggaeton artist. Where are the Cuban reggaetoneras standing against the regime, those who have taken a stand or been in the political spotlight? They don't exist," he said.

With Rodriguez's fragment left out, each singer wrote their part.

"We realized we had a hymn. We decided to change the name and put this phrase, Patria y Vida (Homeland and Life), an allusion to their Patria o Muerte (Homeland or Death), and say 'I count", Yotuel recalled. "'Patria y Vida' means defending life, above all else. Today it is horrible to hear the word 'death', to continue with this doctrine of 'Homeland or Death' is preposterous because what it transmits is: 'Either you're with me, or you die,’ “he added.

Once the song was ready, Yotuel sent it to Babastro. The director had already filmed the video for "Ámame como soy yo" ("Love Me As I Am"), an unequivocal condemnation of the Revolution's 60 years of authoritarianism.

Babastro confessed to Yotuel that he cried for two days after listening to "Patria y Vida." The director was ethically moved and affected by the events of November 27, 2020 in front of the headquarters of the Ministry of Culture in Havana. That protest, in which more than 300 people participated, was over the eviction of members of the San Isidro Movement, including Osorbo and the artist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, who appears in the video for "Patria y Vida" with a Cuban flag.

"Honestly, 27N was the right time for artists to take a position with respect to the Government. I saw the way they were slandered and used (...) I couldn't be with those people who had done that," Babastro said.

The process to complete the song "took a month or so, from when we started until the video was filmed and edited. We started on January 15, and the song came out on February 16," Babastro said.

Necessary voices from Cuba

Yotuel included El Funky and Osorbo for them to share "what they go through and how. In a song like this it was important to include emerging Cuban artists and, above all, those with a social cause," said the singer.

"The title of the song plays with an ultra-communist slogan, because Cubans don't need more death, we need life, because without life there is no freedom," El Funky told DIARIO DE CUBA.

He explained that he poured into the song "a flood of feelings and experiences lived under pressure from State Security, and repression. I expressed those things there."

"Recording the voices, doing our parts here in Cuba and sending them was the easiest part. We went to the studio, recorded our parts and sent the vocals via WeTransfer. The most difficult thing was when it came time for the filming. It was really tough," El Funky said.

"Nobody wants to be exposed to the risk of working with us, because of how rebellious we are here on the island, and because we are persecuted by State Security," he added.

The footage for the clip in Havana was shot in a single day. "The process was really very rushed. We didn't have the budget to film at that time, and my camera was pawned so we could rent equipment, for lights and black fabrics, food and such," photographer Anyelo Troya, responsible for the images filmed on the Island, explained to DDC.

An anthem against the Cuban regime

"There are a lot of people who could have been in it, but we didn't have time to coordinate with all those people's agendas. We had to get it out. It was a song that Cuba needed because it was a time when people needed to sing something all together, to have a shared song, to give the cause a name. And that’s 'Patria y Vida'. It gave the people a motto," said Asiel Babastro.

When the video was released, the ruling party began its attacks and attempts to discredit the artists. The regime's media hurled insults like "jineteros," (hustlers) "ungrateful blacks," "delinquents" and others.

Yotuel responded to the slights by relating the repression he has suffered in Cuba to the international media. "To the Government of Cuba I say: 'this little black jinetero' is going to be in the European Parliament," he told DDC.

At the beginning of the video a Cuban peso note bearing the image of José Martí catches fire and burns up, replaced by a dollar featuring the face of George Washington. "We wanted to reflect that duality today with the currency right at the start, to close by saying that, 'when this is all over, we Cubans are going to restore that Martí and the value of our money,'" Yotuel told DDC.

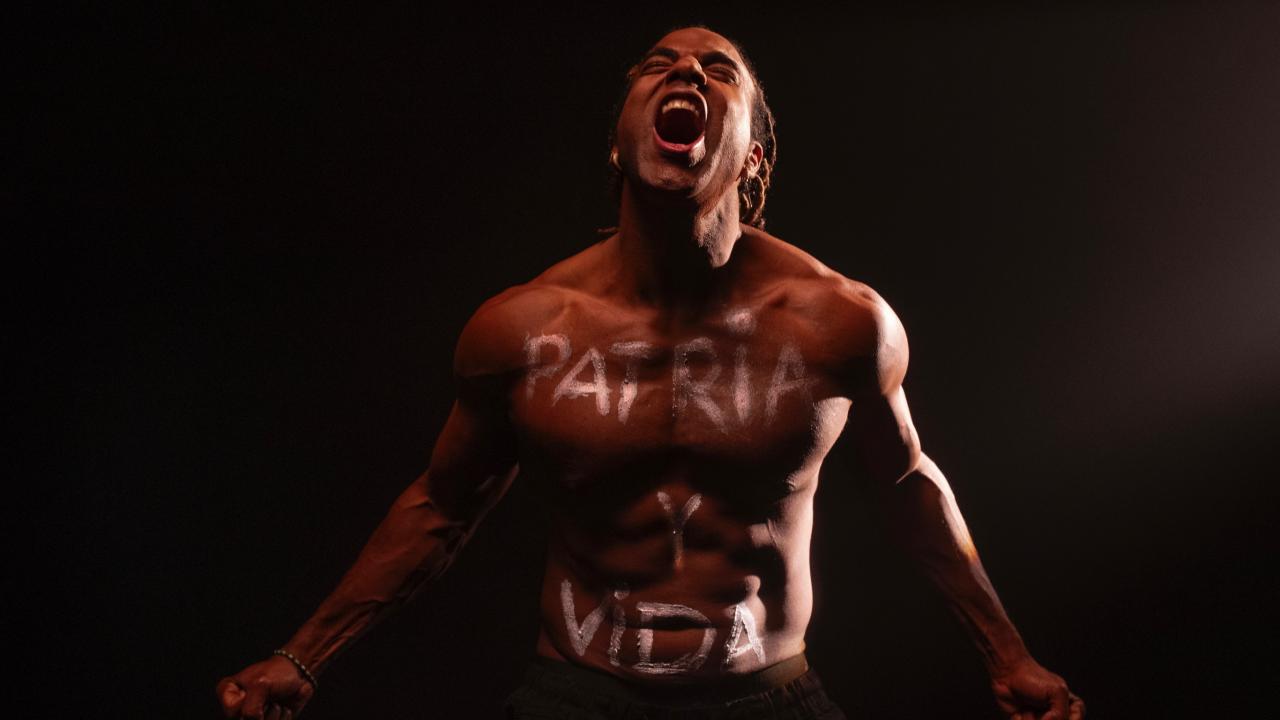

The singer appears in the video with the two words painted on his body: "I used the word 'Patria' on my chest because it always goes on the heart, and 'Vida' on my stomach, reflecting the more feminine part, the part of creation, for those brave women in Cuba," he said in reference to the recent protests on the island led by women.

The regime went from repressing those who wrote "Patria y Vida" on the facades of their houses to Díaz-Canel's appropriation of the hashtag on Twitter. "Just look at how palpable the Revolution's double standard is: Díaz-Canel is using the hashtag," Babastro said. The regime's songs of response and defamatory machinery have been unable to defuse the impact of "Patria y Vida" among Cubans.

Babastro announced that he is making a short film about "Patria y Vida" to be made available on streaming platforms. Yotuel Romero gave Chocolate MC the green light for repartera (Cuban reggaeton) version, and Maykel Osorbo is working on various songs with Cuban musicians and "many international artists who right now don't agree with what we are going through in Cuba."

"We're going to continue making more songs," said Osorbo.