The femicide of Jessica Castillo, on June 15 in Pinar del Río, is only the latest illustration of how the Cuban state is much more efficient at crushing any form of dissent than protecting the country’s women and girls.

The alleged perpetrator of that crime had committed a similar one in 2011. That first victim, Emelinda, was 16 years old. He was 17, and sentenced to 20 years in prison. But, after having served approximately one-third of his sentence, he received probation.

According to Article 89.1 of the Cuban Criminal Code "the court may order the conditional release of the person sentenced to temporary incarceration or correctional labor with internment if, evaluating their individual characteristics and behavior during the their imprisonment, there are well-founded reasons to conclude that they have been reformed and that the aims of the sanction have been achieved without the need to fully execute it; in accordance with the provisions of the law."

Former judge Edel González Jiménez, a jurist with 17 years of experience in the Cuban judicial system and an expert at DIARIO DE CUBA, explains that when such probation is to be granted to the perpetrator of a murder, or a rape, "the protocol indicates that the re-educators, together with the prosecutor, who are charged with evaluating the advisability of the probation before the court, are supposed to ask the victim's relatives for their opinions."

If the case reaches the court and their opinions have not been requested, the court is obliged to stop the case and demand that this step be taken, the jurist added.

In the case of Emelina's confessed murderer, this step was skipped, so the requirement was violated, according to a relative of the victim, who talked to the Gender Observatory of the feminist magazine Alas Tensas (OGAT) and the feminist platform Yo Sí Te Creo en Cuba (I Believe You in Cuba), who shared this information with the DDC.

González Jiménez also explained that in Cuba, before the perpetrator of a murder or rape is released on parole, psychological evaluations are not, in fact, carried out.

"Psychological evaluations of the accused apply when they are going to be subjected to an aggravating situation, when they are going to be deprived of a right, or one is going to be taken away."

The decision to grant parole is up to the court, provided that all the application legal requirements of law are complied with. In the cases of many Cubans who demonstrated against the regime in July 2021, the courts have denied them parole, reductions of two months for each year of their sentences, transfers to less severe prisons, and others provided for under the law, despite the sentence times they have already served.

When Emelinda's murder was revealed (news of it did not come out in 2011), it became known that her aggressor had tried to kill her before. Despite the fact that the former Cuban Criminal Code established sentences of 5 to 30 years of imprisonment for attempted murder, the perpetrator was only fined 1,000 pesos, a relative of the victim told the independent media source Cubanos por el Mundo.

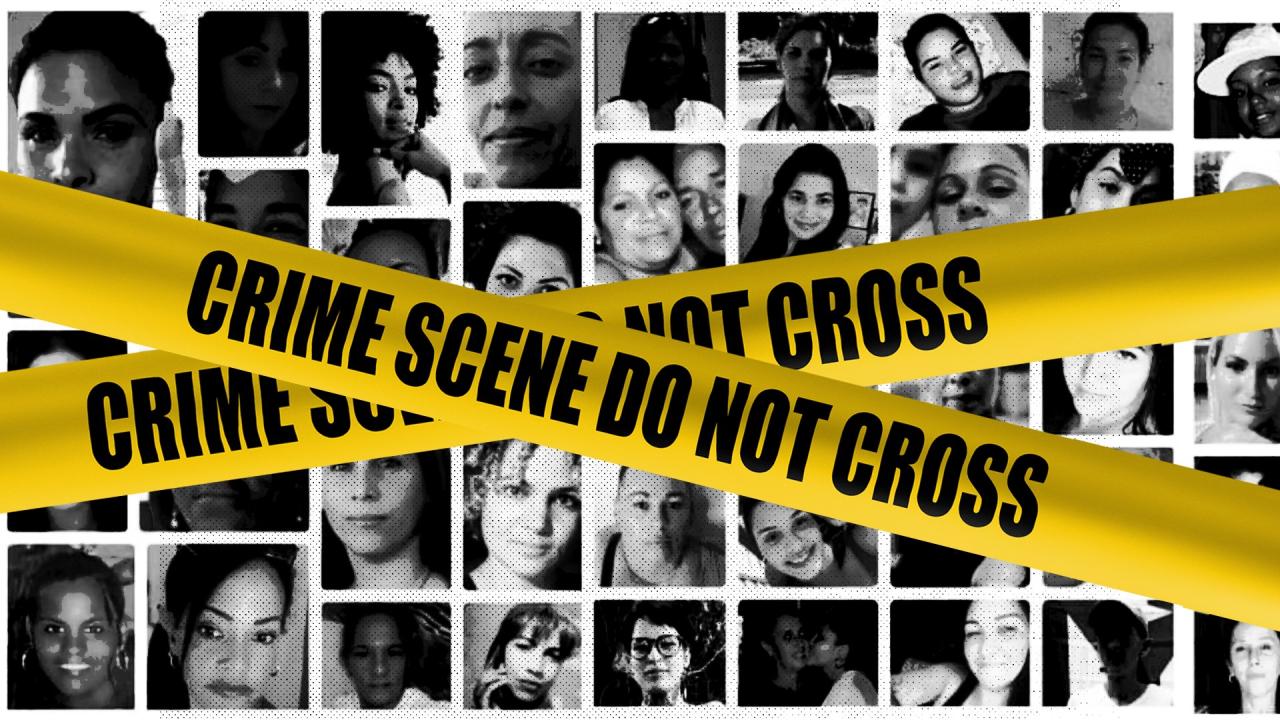

This adolescent's case does not constitute an isolated event. Rather, it demonstrates a pattern of failure to protect victims, or at least negligence, by the Cuban State towards victims of gender violence, standing in contrast to the striking efficiency with it retaliates against any citizen who expresses their dissatisfaction with the regime.

Another clear example is the three-year prison sentence imposed on Maikel Solano Arévalo, found guilty of sexually abusing a girl, handed down a full year after the events and an appeal trial. He was initially sentenced to three years of correctional labor without internment.

The new sanction, imposed on the sexual aggressor by the Provincial Court of Granma, falls within the sanctioning framework provided for in the Criminal Code for sexual abuse against a person under 12 years of age, which is two to five years of incarceration. If Solano Arévalo demonstrates good conduct, he could be released on parole in one year and six months.

Former Cuban judge Maylin Fernández Suris, an expert in family affairs and gender violence, and a lawyer for the DDC, pointed out the delay in the administration of justice in this case, and the failure to issue a restraining order to protect the minor.

Less than a month after the sanction that Solano Arévalo received, it came out that the Cuban Prosecutor's Office is requesting nine years in prison for the influencer Sulmira Martínez Pérez, age 22, for a "crime against the constitutional order" and two for "contempt." The joint sanction requested is ten years in prison.

Martínez Pérez posted material on the Internet in which she criticized the regime and called on people to demonstrate. She has been imprisoned since January 10, 2023, in provisional detention as a precautionary measure, despite the fact that she had no criminal record.

In April, 14 Cubans who participated in the anti-government protests in Nuevitas, Camagüey, in August 2022, received sentences of between ten and 15 years in prison. The toughest, a joint sanction of 15 years in prison, was received by Mayelín Rodríguez Prado, for "enemy propaganda of a continuous nature" (ten years of incarceration) and "sedition" (12 years of incarceration).

Rodriguez Prado, 22, was arrested at her home for posting images on social media of young girls who had been physically assaulted by police officers as they tried to prevent their father's arrest during the protests. Since her arrest she has been in provisional detention, as have the rest of those prosecuted for the protests.

In the same month the regime's newspaper Granma published an extensive article in order to demonstrate that the Criminal Procedure Law, passed in Cuba in 2021, protects women and victims of gender violence. It stressed that the precautionary measures adopted in these cases against the alleged aggressors were to prevent continuations of the alleged criminals' conduct and protect the victims."

"These measures include restraining orders extending to both to the injured party and their relatives or those close to them, in order to prevent the accused from establishing physical contact with them, or any other type," said the state newspaper.

However, in the case of the abused minor in Granma, the aggressor was not provisionally detained as a precautionary measure, despite the severity of the crime and the fact that he was a neighbor of the victim, which left the latter unprotected, as González Jiménez pointed out at the time.

Former judge Maylin Fernández Suris, specializing in family matters and gender violence, recalled in May that the Government of "Cuba has championed its legislative reform on gender violence and the protection of minors, which it carries out through the enactment of the Criminal Procedure Law, the Criminal Code and the Family Code, precisely in response to the calls of international organizations, and to adapt to international parameters."

The application of Cuban law, however, remains lenient towards sexual abusers.

In October 2022 pro-regime singer/songwriter Fernando Bécquer was found guilty of that crime after initially being accused by five victims. The figure eventually rose to 30.

He received a five-year sentence of limited freedom, such that he never went to prison. As DIARIO DE CUBA columnist Lucía Alfonso Mirabal explained in an analysis at the time, in judicial practice, this sentence is usually applied to very elderly convicts, or one with physical disabilities that prevent them from working.

It is a sanction that could have been received by the political prisoner Felix Navarro, age 68, who was sentenced to nine years in prison for his participation in the 11-J protests, denied any reduction in his sentence in light of his age.

It was not until January 2023, after Bécquer uploaded offensive posts on social media, that the Municipal Court of Central Havana revoked his limited freedom sentence and sent him to prison; not for five years, however, but rather for three. At that time the victims found out that the Provincial Court had approved the appeal of the singer, whose songs typically praise and defend the Castroist regime.

In May, images of Bécquer apparently working in communal services, in a blue jumpsuit, were circulated on social media. Experts consulted by DIARIO DE CUBA indicate that this is easily possible, since, given his conviction, if he has demonstrated a good attitude in prison, he very well may have progressed within the prison system and qualified for work.