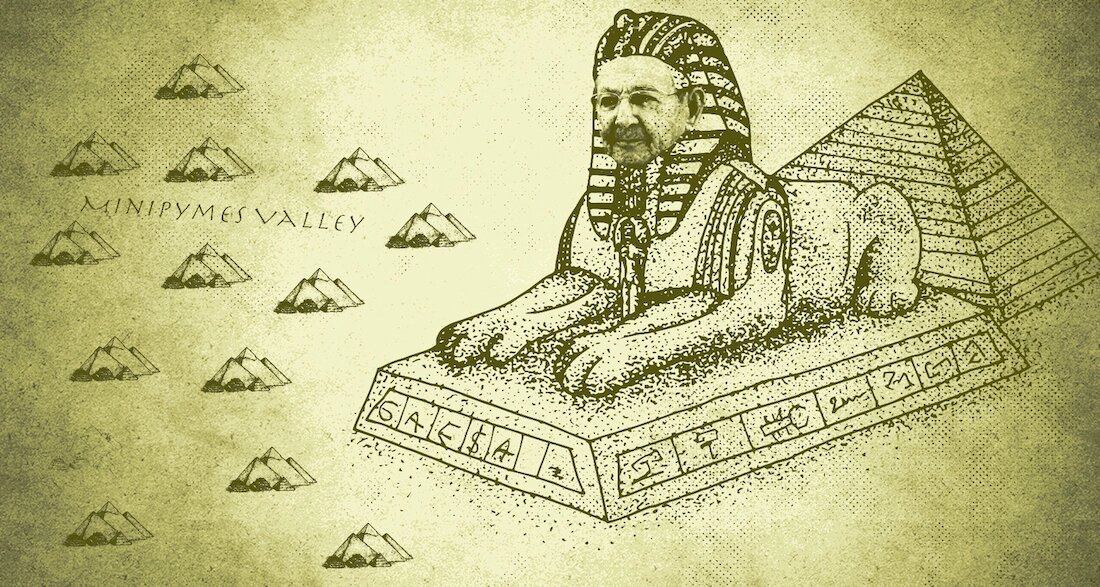

Since Fidel Castro bequeathed absolute rule to the politically weaker Raúl Castro, we do not know exactly who makes up the inner circle of power in Cuba. That transition, in monarchical terms, was a metamorphosis from a centralized pharaonic system — Fidel ruled alone — to a late medieval kingship model, with a primus inter pares (first among equals) forced to share his power with and lean on key figures.

The current power structure, centering on Raúl Castro and his diffuse and not always well-chosen entourage, is ready to change anything it must with respect to the previous regime, as long as it preserves the most important thing: absolute authority within a totalitarian system that, exhausted, is rapidly shifting from ideologically unbending to explicitly repressive.

After the failure of that socialist model, which Fidel Castro was able to sustain thanks to his historical cachet, and Soviet and Venezuelan subsidies, the current rulers know they need to do what the former never wanted to: transform the domestic economy into a fundamental source of resources, which requires, much to their chagrin, granting certain freedoms and degrees of private property.

Desperate, Castroism’s high nobility is seeking to revive the "bourgeois" capitalist class it so viciously annihilated, but without going as far as the economic liberalism successfully deployed in China or Vietnam. The plan is for there to be a bourgeoisie in Cuba, but, to guarantee the status quo, the most powerful members of that nascent class will be chosen by the regime itself, allowing them to thrive economically through MSMEs that will blossom in the shadow of the State and its thousands of ramifications in Cuba's totalitarian society.

Of course, it would be unseemly for the government to distribute, ad hoc, "private" companies among its faithful, as this would render them targets for the terms of the embargo, so it has opted, thanks to the "blockade," to legislate, allowing, in theory, any Cuban to open a small or medium-sized enterprise.

Clearly, this open regulation will be taken advantage of by thousands of Cubans not connected to the regime to start their own business projects and, although the vast majority will fail (this is a universal statistical truth) some will achieve limited success, allowing their founders to "live well" (occasional trips, a modern car, guaranteed food). But rising above this level will be almost impossible without connections and the government’s blessing.

Beyond a certain business threshold, it is a tall order to operate in Cuba without getting on the good side of the powers that be, at least, at the local level (municipal or provincial PCC secretaries, military heads, managers of state enterprises) for two reasons: first, the widespread corruption in the state bureaucracy, where it is better to walk hand in hand with someone powerful; and second, because a high concentration of capital in a political outsider is a threat for the Government. Thus, the successful businessman will have to choose between joining the Castro circus, giving effusive signs of his revolutionary commitment (for example, making donations on the news and being photographed with Díaz-Canel), or to endure being squeezed fiscally and/or administratively until his operation is reduced to a harmless size, if they do not eliminate, confiscate or expropriate it.

Apart from this ordeal awaiting genuine private entrepreneurs, condemned a priori to join the regime, or to remain minuscule or extinct, the majority and most important private companies of the future will be directly connected to the "system," through the son, uncle, nephew or mother of...

Time and again, the spokesmen of Castroism promote what they call "public-private links," a symbiosis that generates legal mechanisms so that the state budget, the money of all Cubans, is transformed, through juicy contracts with MSMEs, into money for some Cubans.

This mechanism will not only serve to enrich the embryonic caste of loyal capitalists, but will also finance and subsidize the related MSMEs so that, through the reinvestment of the profits generated by their favored access to state contracts and other subtle advantages of being "sponsored" —such as having direct access to foreign trade, or receiving foreign currency at preferential prices— they will monopolize the national market and, little by little, displace legitimate private entrepreneurs.

In short, the current political framework and international isolation of Castroism, which seems to have run out of sugar daddies, now requires a national class that generates wealth, but one that does not threaten the pyramid of power with political demands, either now or in the future, when it has become rich.