Anderlay Guerra experienced the "Shakira" at the Guantánamo Combinado prison, where he was held between 2005 and 2009 for "attempting to leave the country illegally." This Shakira was no woman, but rather what he called "the worst method of torture in that place." It consists of handcuffing the inmate's feet and hands, and placing them behind his back, so that he is totally immobilized on the floor of the cell. It is "a very uncomfortable position..." Guerra explained, "and when you try to move, you move your hips. Hence the ironic name."

Guerra, an independent journalist, said he saw men urinate and defecate on themselves after 24 and 48 hours in this position. "This torture has different variations," he explained. The chain that binds the hands and feet can vary in length. If it is very short, one is left with nothing but his chest stuck to the dirty, damp and stinking floor, crawling with insects and rodents.

The prolonged use of handcuffs as a form of torture has been widely reported and condemned by dissidents, especially the Shakira technique.

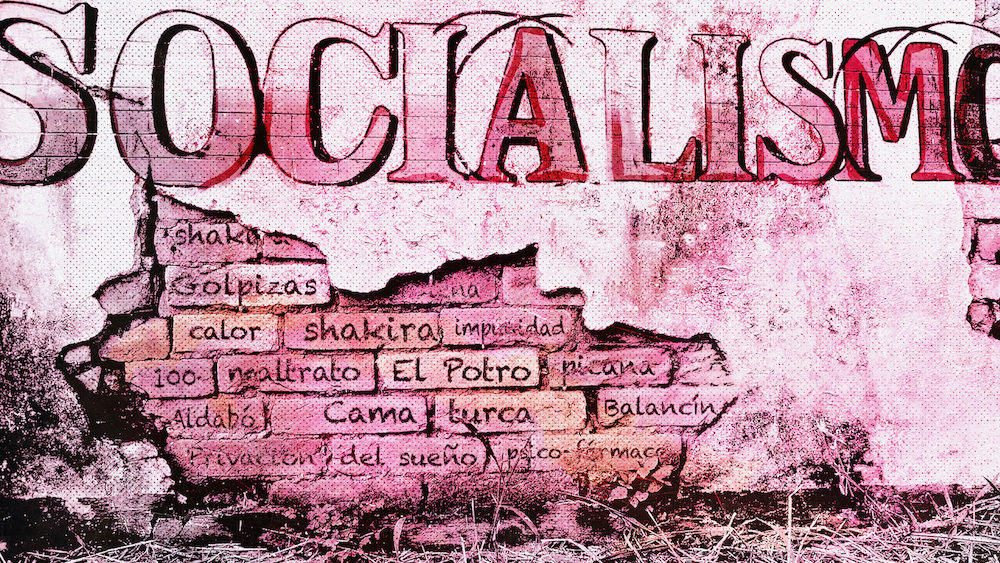

While under National Socialism certain ethnicities were the victims of State repression, under Communist systems, like Cuba's, targets are chosen for ideological reasons, and part of the dissident population is singled out for torture and degrading treatment. Far from the idyllic narrative prevailing in part of the planet, torture is just one more brick used to construct Cuban socialism.

The Shakira and other methods involving the prolonged use of handcuffs

Another version of the Shakira consists of suspending the inmate "from the ceiling of the cell, with chains," which inflicts skin lacerations, especially on the wrists and heels.

"The decision to release him is made by the guards, at their discretion. If the prisoner is very 'rebellious' or the 'misconduct' is considered very serious, then they are left like that for longer," said Guerra. In his experience, they are crueler towards political prisoners who shout anti-government slogans or go on hunger strikes to demand medical assistance, or "prisoners' rights."

The practice is not new. Francisco Osorio, a Guantanamo dissident who was imprisoned in 1992, had already heard about the Shakira, also called the Balancín (see-saw). This torture technique, however, seems to be widespread and a longstanding practice in the Cuban regime's prison system.

Guerra heard that it was perpetrated at the Kilo 8 prison, in Camagüey, and at Boniato, in Santiago de Cuba, "and later it reached Guantánamo."

Following the Sunday demonstrations by the Damas de Blanco (Ladies in White) and other accompanying groups during the "thaw" in diplomatic relations between the US and Cuban governments, the use of the Shakira was also reported. In Havana, more than a form of torture, it referred to the type of handcuffs used to incapacitate the protesters.

The sessions allegedly took place at the Tarará Police Academy. There, in addition to subjecting the victims to uncomfortable positions for hours, groups of both men and women in uniform beat them.

In June 2021 a report came in from the Mayabeque province. Zuleidis Gómez told the independent press that at the high-security prison in Guanajay her husband, the activist and reporter Esteban Rodríguez, recently forced into exile by the regime, was shackled with "Shakiras."

"He is handcuffed, hands and feet, 24 hours a day," the woman reported on social media. "They are holding him in solitary confinement. The pressure is getting to him."

Although in Cuba there are no studies on the physical and psychological consequences of this type of torture for victims, the specialist in physiatry Miguel Ángel Ruano believes that an analysis of injuries due to the prolonged use of handcuffs on the island would yield similarities with studies on the topic like the one conducted by Dr. Angélica María Losada in Colombia.

Ruano, also a doctor in Neuroscience, recalled that the lesions are evidenced by changes in color and edema, losses in the continuity of the epidermis and/or dermis on the wrists and the distal third of the forearms, as well as numbness, cramps, paresthesias and limitations in strength, flexion and movement.

In June 2021, Leticia Ramos, a representative of the Ladies in White, reported that political prisoner Virgilio Mantilla was subjected to another form of torture involving bonds or handcuffs, known as El Potro. In a punishment cell at the Kilo 8 jail in Camagüey, her hands and feet were bound and she was secured to a post.

At the Las Tunas Provincial Prison another technique was used, called the Cama Turca, or "Turkish Bed." Inmate Yunier Almaguer spent six days on a bunk, without a box spring or mattress, with his feet and hands bound.

In an audio message shared by the Cuban Observatory of Human Rights, a witness explained that on the bunk "they chain you like Jesus Christ, they throw you there as if you were lying down." He clarified: "but the bed does not have a board or anything; they hang you there for however many days they want to, with your hands and feet cuffed."

Today more than 800 Cubans are being held, or have been sentenced, for political reasons on the island. Here the Socialist Revolution sets another record: the most prolific producer of political prisoners in the Western Hemisphere. The figure was issued by the NGO Cuban Prisoners Defenders, in its first report of 2022. Tales of torture could multiply in the coming months.

High temperatures, sleep deprivation and beatings

The Cuban regime recognizes that torture is practiced on the island ... but, it claims, only at the US naval base in Guantánamo. In a recent episode, the official program Con Filo mentioned some of the techniques documented in this report, like temperature changes and sleep deprivation, but at no time did it admit that this is something that also happens in the Castroist police-penitentiary system.

Arianna López, the head of the Julio Machado Academy in Villa Clara, however, has suffered them. According to her, in March 2020 she was taken, handcuffed, to an interrogation room of the Provincial Investigation Unit. Inside, the air conditioning was on full blast.

Dr. Miguel Ángel Ruano explained that when an individual is tortured by exposure to low temperatures, they can suffer "from the generation of facial paralysis, to symptoms such as sneezing, headache, general malaise, nasal congestion, cough and sore throat."

The Cuban doctor explained that "drastic changes in temperature cause the body's defense mechanisms to fail, and diseases spread, because the bacteria and viruses associated with the respiratory tract thrive in cold and humid environments." With sudden changes in temperature, the likelihood of contracting viral and bacterial diseases increases greatly.

According to Arianna López, the soldiers went in and out, pretending that they had forgotten about her. "Some turned off the air, and it was very hot, others turned it on, and it was very cold." In October, the activist was arrested again and the scenario was repeated, this time with dissidents Maidelin Toledo, Yenifer Guevara, Yenifer Casteñeda and Donaida Pérez.

After beating them, on the head and ribs, at the Placetas police station, they "put them in the sun for a long time," and later took them to "a cold room." López is clear about what happened: they were tortured.

Ruano explained that while high temperatures favor gastrointestinal pathologies, low temperatures favor respiratory and cardiovascular ones. "One of the most important effects of cold, or sudden changes in temperature, from warm to cold, is vasoconstriction, which produces changes" at the cardiovascular level, increasing blood pressure and heart rate. "It increases the probability of myocardial infarction in patients at cardiovascular risk, and favors the formation of blood clots."

Exposure to high or low temperatures has been one of the best-known techniques taught by KGB and Stasi advisers to their Cuban allies since the beginning of the Revolution, perhaps due its "white torture" nature: it leaves no visible marks.

In 1960, the anti-Castro figure Ángel de Fana was taken to the first headquarters of the political police, in Miramar. "Completely naked, and with my head covered, they aimed an air conditioner at me. I started to shiver," he stated in an interview with the Spanish newspaper ABC.

In that same publication Luis Zúñiga recalled the sleep deprivation to which they subjected political prisoners who, like him, refused to participate in Castro's indoctrination plans. "At the Boniato prison, they subjected us to electronic noise 24 hours a day to drive us crazy," he said. It was horrible. Out of desperation, we banged against the doors' steel plates."

Freelance journalist Mary Karla Ares also suffered sleep deprivation, but decades after Zúñiga. In May 2020, she was isolated for four nights in the Guatao women's prison, "in a cell with only one window open to the sky."

"I had no contact with anyone, except when they brought me food. After eating in the afternoon, I saw no one else," she shared for this report. The first night the guards left the cell light on. Around 9:00 PM, Ares started screaming for them to turn it off. She needed to sleep. "After a while a soldier came by and simply replied that he couldn't do it."

"I was like that for 96 hours. They didn't even turn off the light during the day. Night after night, I asked the guards for the same thing, but they no longer came by my cell," the young woman recalled. Those were days of great mental exhaustion."

Dr. Ruano states that "extreme sleep deprivation can lead to disorientation, paranoia, and hallucinations." In the case of Ares, at the same time they interrogated her, one to three times daily, about her political activism, "personal issues, and even relationships."

Ares also mentioned being taken out to the sunroom as another torture: "many times they took me out around noon, and it was hard after spending so many hours locked up in the cell. The sun burned you, very hard, and you could hardly see."

Medicine that does not cure

The use of medicine and clinical facilities for torture and ill-treatment has also been documented in recent Cuban history. Political prisoner Raudel García reported that in 2012 he suffered an anxiety attack at the prison at 100 & Aldabó that believed was triggered by drugs placed in his food.

About his time in captivity, and trials within the socialist legal apparatus, he wrote the book The Challenge of Living in Cuba, published at the end of 2016. "At that time I was still far from knowing many things that are evident to me today," he explained for this report.

"All of us who have been to 100 & Aldabó will undoubtedly agree that it's a place designed to break anyone psychologically," he added. "I witnessed many in the same cell with me, when they had been there for about 30 days, suffer from psychological symptoms of suffocation. Others could not stand the confinement, and tried to commit suicide. In my section the normal thing was about three or four suicide attempts per month."

"Today, I'm convinced that the nervous breakdown I had was induced," he said. "No doctor who has treated me in the United States believes that it was the product of a natural process. Perhaps it would have been 'natural' during the first 30 to 40 days of captivity, not afterwards."

García, now in exile, speculated that, based on the symptoms he had, it is very likely that they put into his food "small doses of some psychotropic drug that, over time, created an addiction in my body."

"My body's response to its absence would be, naturally, an attack, which was characterized by a high level of anxiety. Within 72 hours of my first symptoms, I was totally unable to sleep and started suffering tremors in my hands and feet. It was horrible," he reported.

Then began the mouth and nose contortions and nervous tics. Raudel García had seen the same symptoms in alcoholics who were admitted to undergo a withdrawal process. "My symptoms were exactly the same, only I'm not an alcoholic," he said. "I overcame the crisis by the grace of God."

For three weeks he was in that state, without receiving medical assistance in prison. Only after he overcame his nervous breakdown, and while he was still at the 100 & Aldabó facility, did political police officers transfer him to Forensic Medicine for a diagnosis.

"The military psychiatrists said that there were aftereffects, so he would continue to be treated. The main one was with sleep." First at the Valle Grande Prison, and later at the Prisoners Ward of the La Covadonga Hospital in Havana, a large and windowless pavilion, for a year they administered drugs to allow him to sleep. The doses were increased months later, at the State Security Ward at Finlay Hospital.

"Within a few weeks my body had already assimilated those doses, which is when they replaced the medications with stronger ones, on which I am dependent to this day." Much later Garcia managed to lower the dosage of the drugs, "but I couldn't get off them. Now, they no longer allow me to sleep, but I can't stop taking them either."

"They gave me the most toxic medications, to the point that, in my first year in the United States, I had a clot in a vein due to all the toxins in my body," he said in an interview with América TeVé.

García, who says that he still suffers from the effects of this medication, observed in May 2021 that the protestor and artist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara may have gone through something similar, referring to the young man's forced internment at the Calixto García Hospital in the Cuban capital.

Upon leaving the medical center where he remained incommunicado, and undergoing psychiatric evaluations, Alcántara described the month he was "kidnapped" as "tough."

At a panel discussion sponsored by the Miami-based Cuban Democratic Directorate, Dr. Alfredo Melgar stated, regarding the artist's case, that "psychiatry and medicine" are used in Cuba as weapons "to break dissidents."

Daniel Llorente experienced this first-hand. On May 1, 2017 he ran through the Plaza de la Revolución, which had been prepared for the start of the march and speeches for International Workers' Day, waving an American flag and shouting "Freedom for the people of Cuba."

He ended up being immobilized by soldiers dressed in civilian clothing, a moment captured by the foreign press covering the annual celebrations organized by the Communist Party. Accused of disturbing the peace and resisting arrest, he spent a month behind bars, and on May 30 he was confined to the Psychiatric Hospital of Havana. His son, Eliezer Llorente, then a teenager, stated that he had never received any diagnosis justifying this imprisonment. He remained for a year, however, at that medical center.

An attentive reader of Foucault, Castroism not only uses its military facilities, but also its clinics, to break detainees. Operatives are not lacking in those ranks; the regime recently declassified the identity of oncologist Carlos Leonardo Vázquez, an agent in the service of the political police for more than 25 years.

Biologist Ariel Ruiz Urquiola reported that, at a Cuban hospital where he was imprisoned in 2015 for his political activism, he was inoculated with the HIV-AIDS virus.

Evicted, and in a wheelchair, the Lady in White Xiomara Cruz reached the United States in January 2020, where her family doctor stressed that, in addition to a collapsed lung, and very little muscle mass, there were bacteria in her body, apparently inoculated in Cuba while she was hospitalized there.

There are also accounts of patients being denied medical care for political reasons. In May human rights activist Yoel Pérez Bravo was admitted to the Manuel Fajardo Military Hospital in the city of Santa Clara. He had Covid-19. Although the lack of medicine and oxygen on the island worsened the health crisis for everyone, in the case of this dissident, his associate Osney Quintana reported that the political police ordered that he not be given the necessary medicines, at least initially.

Later it came to light that, during bouts of fever, cough and shortness of breath, they only gave him medication when he started to have tremors.

The denial of medical assistance and medications is a recurrent complaint by prisoners in Cuban jails.

"Prison, in itself, is torture"

Yaxys Cires, strategy director for the Cuban Human Rights Observatory (OCDH), believes that "both internally and internationally, the scope of the concept of torture has not been understood. Many people think of those corporal punishments frequently depicted in movies or history books, but in truth the torture goes beyond that; even psychological."

The issue is addressed and clarified in the widely-recognized Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment: "any act by which serious pain or suffering is intentionally inflicted on a person, whether physical or mental, in order to obtain from him or a third party information or a confession, to punish him for an act he has committed, or is suspected of having committed, or to intimidate or coerce that person or others, or for any reason based on any type of discrimination, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by a public official or other person in the exercise of public functions, at his instigation, or with his consent or acquiescence."

"Taking this concept into account, the most frequent torture in political prison is the fact that it is imposed as punishment for having exercised one's human rights; that is, prison itself is a torture," Cires said.

"There are political prisoners who, when free, have reported frequent physical threats during their captivity to get them to incriminate themselves, to break their morale, to persuade them to abandon their political ideas, or activism, or to leave their country. They make them believe that they are alone, or that their family could suffer consequences," he added.

In his view, prison for political reasons is "abominable," regardless of whether the prisoner suffers corporal or psychological punishment, "which is also recurrent, especially the latter." Cires recalled the psychological abuse suffered by the visual artist Hamlet Lavastida during his three months in detention in 2021 as a glaring example.

"I agree with Alejandro Gonzalez Raga, former political prisoner and founder of the OCDH, when he says that Cuban law does not combat torture, but rather protects it, both when it allows someone to be sent to prison for exercising their human rights, and when repressive officials act with total impunity," stressed the fellow lawyer.

"In the case of bodily torture, such as beatings, the regime is careful to prevent them from being documented, beginning by making it difficult for medical professionals, both inside and outside the prison, to voice the truth. Even so, there are more and more accounts of physical abuse," acts of repression in response to the protests that shook Cuba in July 2021.

Stories of beatings of detainees and inmates have been common from the very beginning of the Revolution, and reach down to the present, with chilling details. Pastor Lorenzo Rosales, from Santiago, imprisoned in Boniato since the anti-system demonstrations of 11-J, suffered it, according to a witness who preferred not to reveal his name.

The source, "one of the guards who urinated" on Rosales' head in the early hours of July 14, when he was transferred to the Versalles police station, contacted human rights defender Mario Félix Lleonart.

"We had no water," he wrote to him via Messenger, "and we thought we had killed him with the beating we gave him on the way." The stranger revealed that he did not want to abuse Rosales, but, if he had not participated, he said, "I would have put the dead man." In his final messages, the alleged soldier warned: "they're prepared to kill Pastor, so that he can't share everything that has been done to him. Any day now another inmate could kill him, or he could turn up dead."

Stories like this will multiply as those arrested for the protests of last July are in more contact with their families, or are released. We are poised to bear witness to a new set of accounts of the horrors of the Revolution.

Even with these accounts revealing its lack of values, a few months ago the socialist state news, in a Russia Today report, criticized the British government for torturing Irish prisoners. In 1978, the audiovisual work explained, Great Britain was brought before the European Court of Human Rights, which ruled that prisoners had not been tortured, but rather had been subjected to inhuman and degrading treatment.

When someone confronts it, and the Cuban tyranny deigns to respond, what technicality will it invoke to justify its torture of its prisoners? Will it continue to act as if nothing were happening on the island? Will the free world continue to do so too?