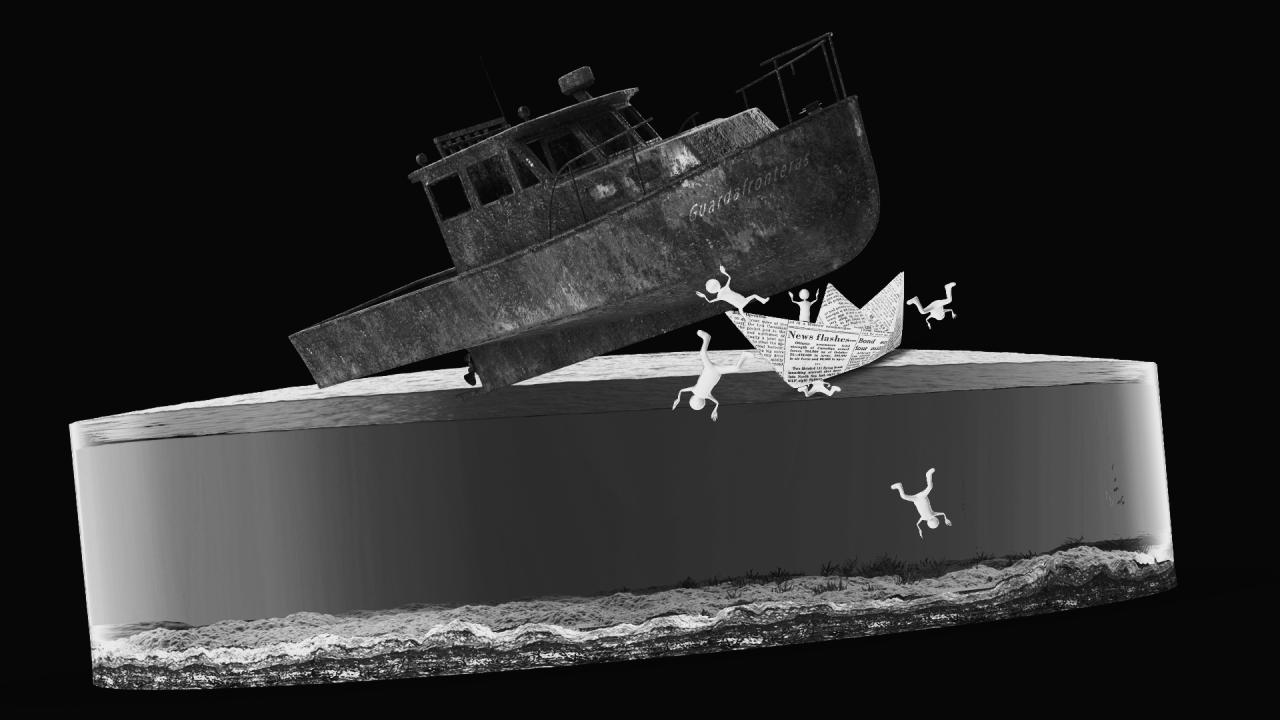

While the Cuban regime blames the United States for events such as the recent sinking of a boat near Bahia Honda in which seven people died, including a two-year-old girl, accusing it of encouraging irregular migration and human trafficking, it fails to recognize that, if there is human trafficking, then there are victims, and military intervention to stop these illegal operations should seek, first and foremost, to protect those lives.

In this regard, there are international protocols that the Cuban regime has violated in all those cases in which people have drowned while trying to leave the country. These events were executions; not extrajudicial, but arbitrary.

The protocols ignored by the Cuban government establish that in these cases it is necessary to make every effort to protect the life, dignity and rights of the victims, unless they manifestly cease to do so and become active aggressors. This was not the case: neither the Cubans who attempted to emigrate to the U.S. in an irregular manner aboard the speedboat at the end of last October, and those aboard the tugboat 13 de Marzo in 1994, were unarmed, and among them were women, children and elderly people.

The Palermo/2000 "UN Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children" is complementary to the case of the sinking in Bahia Honda. It required the Border Guard to escort the boat and to inform U.S. institutions in order to operate in concert to protect the emigrants' human rights.

The protocol calls for protection in cases similar to human trafficking, or in which there are victims of organized crime, suggesting parameters for police/judicial cooperation and information exchange between countries involved in the migration phenomenon.

As Cuban-American congressmen recently pointed out in a letter to the US representative to the UN, in which they asked her to condemn the sinking of the boat, the Cuban State has not placed itself under the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court, whose Article 7 defines as "crimes against humanity" actions such as murder, torture, persecution, "imprisonment or other severe deprivation of physical liberty" or other "inhumane acts of a similar character intentionally causing great suffering or serious injury to the body or to mental or physical health," committed "as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against a civilian population."

The Cuban State is, however, a signatory of the aforementioned UN protocol, and has adapted its provisions to the national context by means of internal directives of a military nature, not published in the Gazette of the Republic.

The observance of this Protocol entails compliance with the "Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials," adopted by the Eighth United Nations Congress on the Prevention of Crime and the Treatment of Offenders, held in Havana from August 27 to September 7, 1990; with the Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in its Resolution 34/169 of December 17, 1979; and also with the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in Resolution 45/158 of December 18, 1990.

The absence of legal prosecution against the border guards responsible for the sinking of vessels in which dozens of Cubans have died, in violation of protocols signed by the Cuban State, and national provisions, demonstrates that not only have they acted with the regime's consent, but also on its orders.

The Cuban regime, which exhibits such concern for children and is a signatory to the International Convention on their rights, and recently threatened parents who take minors on their illegal departures from the country, has ignored the presence of those same children on the vessels it has sunk.

These conflicts involved in illegal departures and human trafficking, their cost in the lives of these people aside, are not classifiable as extrajudicial executions; to be so, a direct and unequivocal political intention to kill an adversary of the instituted power, without a trial, and/or without the existence of a death sentence ordered by a final judicial sentence, would have to be demonstrated. This is not the case here.

However, these are arbitrary executions intended to serve as criminal deterrents. By means of these sinkings, for which the regime goes unpunished, it seeks to dissuade Cubans from undertaking illegal departures. It might seem contradictory, considering that the regime itself has resorted to encouraging emigration, more than once in history, to reduce pressure in the Cuban pressure cooker and, along the way, have more Cubans sending remittances to the Island, one of the main sources of income for the Cuban State.

The most recent example is the Nicaraguan visa exemption for Cubans decreed at the end of 2021 by the regime of Daniel Ortega, an ally of Miguel Díaz-Canel. Cubans who take the migration route through Central America leave the country legally, which does not make the government look as bad as those who take to the sea.

Meanwhile, the flights that take Cubans desperate to emigrate to Nicaragua generate millions of dollars for tour operators, travel agencies and charter companies, from which the regime might be taking a cut.

The Cuban regime strives to put the spotlight on the US, which it accuses of not complying with migration agreements, and of not delivering the number of visas it has committed to in order to guarantee legal and safe migration, but it knows that this is not the solution.

These agreements establish the annual delivery of at least 20,000 visas. Last October alone, 29,872 Cuban migrants arrived in the U.S., for an average of 963 each day, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection statistics.

In U.S. fiscal year 2022, from October 1, 2021 to September 30, 2022, 224,607 Cubans arrived in the U.S., approximately 615 per day.

This means that not even the U.S.?s complete compliance with its visa delivery commitments will be able to stop irregular migration in Cuba, which is going through its worst migration crisis in decades.

Illegal departures by sea will continue, despite warnings from the U.S. Coast Guard that migrants will be deported. Without investigations by independent international bodies, or strong condemnations of the regime for deadly incidents such as that in Bahia Honda, they will continue to occur.