What criteria were taken into account to establish the order of the legislative agenda in Cuba? This was one of the questions appearing in an article published on the official Cubadebate website on January 16.

According to Justice Minister Oscar Silvera Martínez, quoted in the aforementioned article, "the dates planned were based seeking a balance between the country's priorities and the actual possibilities of the National Assembly and its dynamics."

Considering the issues prioritized and relegated, as well as the number of executive orders slated on the agenda, one would have to ask whether by "country" the Minister of Justice was referring to all of society, or just those in power.

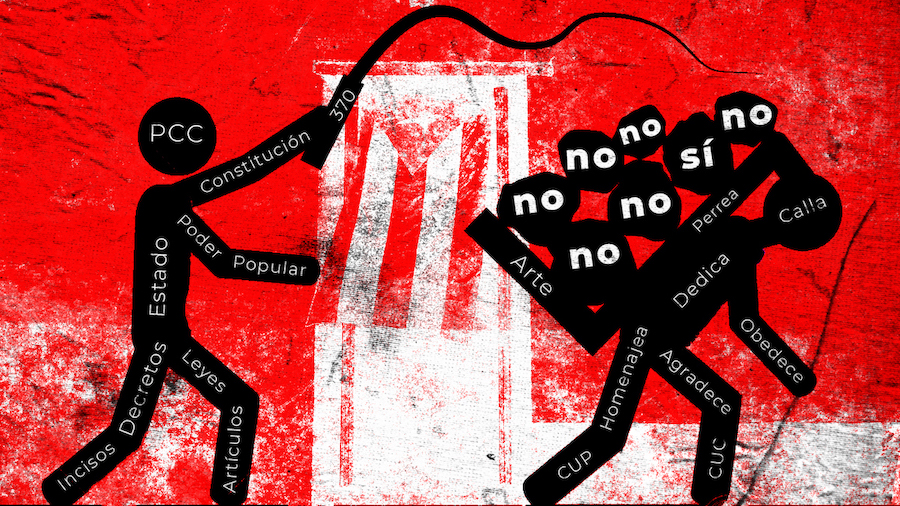

"This is a legislative calendar for those in power, and not for society," concluded political scientist Manuel Cuesta Morúa. "The calendar includes 14 issues, 10 of them corresponding to the regime's organisation chart, assigned priority on the agenda to oil an apparatus that ignores governance and the inclusion of all the actors involved in political decisions that this would entail. Only three (issues) border on the social, and I say 'border' because it is not clear if they were included to restrict or liberalize them. And only one has to do with the people: that which addresses constitutional rights. There, I imagine that they will seek to control, as much as possible, the public and political scope of popular actions."

Lawyer Julio Alfredo Ferrer Tamayo concurred, underscoring that something as vital to the people as the Housing Law is not slated for approved until December. Others, such as the Penal Code and the Execution of Criminal Sentences Law, have been put off until July 2021. Those covering Aliens, Identity, Citizenship and Migration will be issued "in the far-off April 2022", and the Associations Law has been scheduled for July 2022.

Journalist Boris González Arenas's main interest is "the Law of the Popular Courts, modifications to the Law of Criminal Procedure, and the 'something' that will be approved to 'implement the provisions of Article 99 of the Constitution, referring to the possibility of citizens' accessing judicial channels to claim their rights' (transitional law 12.)"

González Arenas points out that attention should be paid to what is passed, because "the protection of constitutional rights, alluded to in a vague way in the new Constitution (Article 99), is a necessity without which our status as citizens, and even human beings, is not recognized."

He harbors no hope about what is ultimately formulated, after the approval of the new Electoral Law, because it "confirmed what we all feared: the practice of suppressing constitutional rights with complementary laws, a pillar of Castroism, will continue. Though the new Constitution guarantees in its Article 204 the citizen's right to participate in the administration of the State, and the right to vote freely, the Electoral Law, with the maintenance of the Nominations Commission and its functions, thwarts both possibilities."

Lawyer and activist Hildebrando Chaviano observes that, based on the order set down in the legislative schedule, Cuba's elite may not have decided which paths to take yet, and could be waiting to see how events unfold on the island, and in the world. "Core matters, like the Companies Law, the Trading Companies Law, the Land Law, and the Associations Law have been postponed until 2022. And the Foreign Investment Law and the Culture Law have been tabled until 2023. There is no plan for the country, but rather one for a political party that dominates the legislature."

Why so many executive orders?

One worrisome aspect of the schedule, for Ferrer Tamayo, is the excessive issuance of executive orders: 27 in total.

The lawyer explains that executive orders (or “decree-laws”) are equivalent in force to a "law, issued by the executive power, but without any prior intervention or authorization by a congress or parliament. "This type of law is usually provided for in the legal system, but to be issued in certain cases, in urgent situations where obtaining authorization for the issuance of a law itself is not viable, although they require validation by a legislative body, usually within a short period of time."

Legally valid regulations, issued by a de facto government, are also thus termed."

The lawyer wonders why there are so many executive orders on Cuba's legislative agenda, and what the emergency situations are that make them necessary.

Concern about this excess also appears to have been present even in the official media, since one of the questions included in the Cubadebate article on the legislative schedule was whether the disproportionate issuance of executive orders could gut the National Assembly's legislative agenda of content.

"Precisely to limit the excessive creation of executive orders, the National Assembly approved the legislative schedule that defines the number of laws and executive orders that will be issued during the terms," was the response offered readers. A supposedly sound distribution of executive orders during each legislative term, however, does not resolve the excess that there will be in the end, especially because, as lawyer Ferrer Tamayo notes, we do not know what these "emergency situations" requiring this measure are, or how many there will be.

"For a totalitarian system, decrees and executive orders are the most effective tools"

It is striking that a government without any legal opposition, supposedly governing with the support of the majority of citizens, needs to do so through executive orders.

Hildebrando Chaviano believes that, although they have control of the National Assembly, Cuba’s rulers do not want to run the risk of a controversial bill getting held up there. Chaviano is convinced that "for a totalitarian system, decrees and executive orders are the most effective tools to impose their will, even if they violate the Constitution and other laws."

Ferrer Tamayo offered an example, referring to Executive Order 370 of 2018, which is being used to stifle critical voices within Cuba. The lawyer cited its Article 1: "The State promotes the development and use of Information and Communication Technologies, with the aim of them constituting a political force."

As Ferrer Tamayo explains, in these executive orders "restrictions and exclusions for political and ideological reasons" are evident, such that they violate the provisions of Article 54 of the Constitution: "The State recognizes, respects and guarantees the people's freedom of thought, conscience and expression."

They also violate Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, of which the Cuban State is a signatory: "Every individual has the right to freedom of opinion and expression, which includes the right not to be mistreated for their opinions, and to investigate and receive information and opinions, and to disseminate them, without limitation, by any means of expression."

Ferrer Tamayo believes that this glut of decree-laws entails "a violation of constitutional precepts by a lesser rule," which allows the government to ignore "the opinions and judgments of the majority."

To these consequences Hildebrando Chaviano adds the deferment of necessary and inevitable changes, as "hunger and repression will continue to be the order of the day, because the new legislation, they have announced only aims to refine the same failed schemes used to date."

Cuesta Morúa perceives a greater disconnect between the government and the populace, and an early erosion of the government's legitimacy at its two key levels: administration and politics. "The first, expressed in the government, and the second in the Communist Party, which is not an elected body in the nation. In all this, the important thing for me is that possible constitutional action be on the side of the citizens, against a government of decrees."