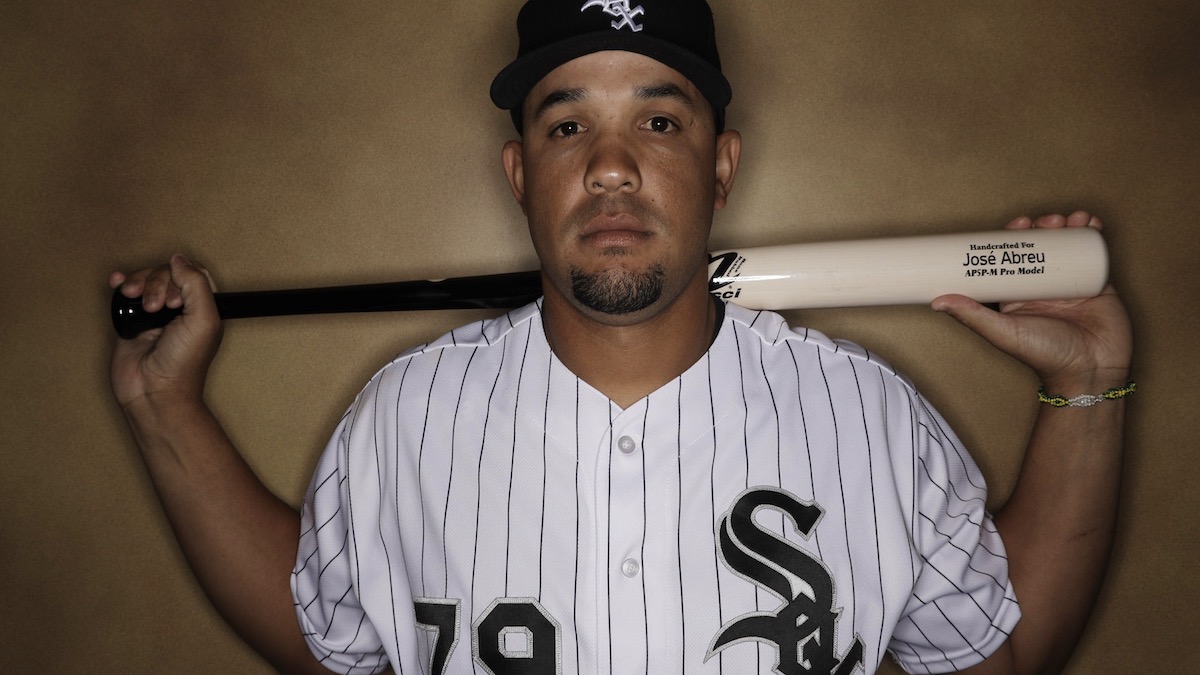

José Abreu heads the list of candidates for the American League's Most Valuable Player in 2020. The star from Cienfuegos was the leader in RBIs (60) and slugging percentage (.617), second in home runs (19), fourth in batting average (.317), fifth in On Base Plus Slugging (.987), in addition to playing in all the White Sox' games (60) and leading the team, after years of languishing, into the fall.

His personality and work ethic now permeate Chicago's bench, where he leads a generation of young stars by example.

Cuba's official press, however, does not cover him.

Nor does it report on any players from the island who play in the Major Leagues: Randy Arozarena, Yandy Díaz, Aroldis Chapman, Yulieski Gurriel, Aledmys Díaz and Adrián Morejón, who, starting today, will play in the Division Series of the world's premier baseball league.

It is as if the media in the Dominican Republic refused to talk about their young superstar Fernando Tatis Jr. This is the parallel, isolated world in which Havana's duplicitous buffoons for leaders force the vast majority of Cubans to live.

Since July, at least, according to Higinio Vélez, president of the government's Cuban Baseball Federation, plans have been "studied" to allow the island's players who compete in the Major Leagues to return to the national team. Aside from the immorality of said proposal (as each Cuban player, regardless of where he plays, and whatever he believes, should have the right to be a member of the national team, based exclusively on his athletic achievements) is a weather balloon of a news story floated by schemers at the Communist Party, specialists in taking one step forward and two steps back.

And not only because they are hiding their true intentions - to control Cubans who they have been unable to - but because they know that such a decision does not depend only on them, but on the terms of a US embargo that they themselves fomented.

Reporting on the play of Cubans in the Major Leagues, on the other hand, is something that is in their hands. Would it not be a noble and simple step towards restoring some measure of respect and normalcy, one that would help ease the tension in which we have been forced to live for decades? Why don't they take it? The answer is simple: because for the comrades, all those players are still traitors, sell-outs and "worms", the same "scum" that, if they could, they would throw eggs at and ban from the country.

Don Higinio Vélez may now say on television that "we are all Cubans. We open our arms", but, if this was really their position, the regime's behavior would be totally different. Because what we are talking about here is a nation split in two by a set of leaders that do not even have the courage to recognize that they are the architects of the division.

At least Fidel Castro, emboldened by his dictatorial ego, spoke of "free ball" vs "slave ball", and, on May 19, 1962, orchestrated Resolution 83-A, by which he abolished professional baseball on the island, exalted himself as the sole master of all dugouts, and proceeded to expel from the game anyone who did not agree with the new policy.

At least Fidel Castro had the audacity to head a regime that, without even blushing, printed headlines like this one, from Orientations for our people about how to treat swines, degenerates, traitors, and turncoats abandoning their country, which inspired our headline today.

The dictator's successors, on the other hand, are less daring, and more serpentine. They say that their arms are open, but they believe the same thing as the late leader they still venerate, and this is why they do not print the names of any of those Cubans who have escaped from their fold. They have replaced insults with a complicit silence regarding the cultural genocide that they themselves perpetrate.

It has been said so many times that it is almost a cliché: since its advent in Cuba, when the pro-independence patriots made it their own, and Spain's Capitán General decreed its prohibition, baseball has been a mirror of nation's reality. And it still is.